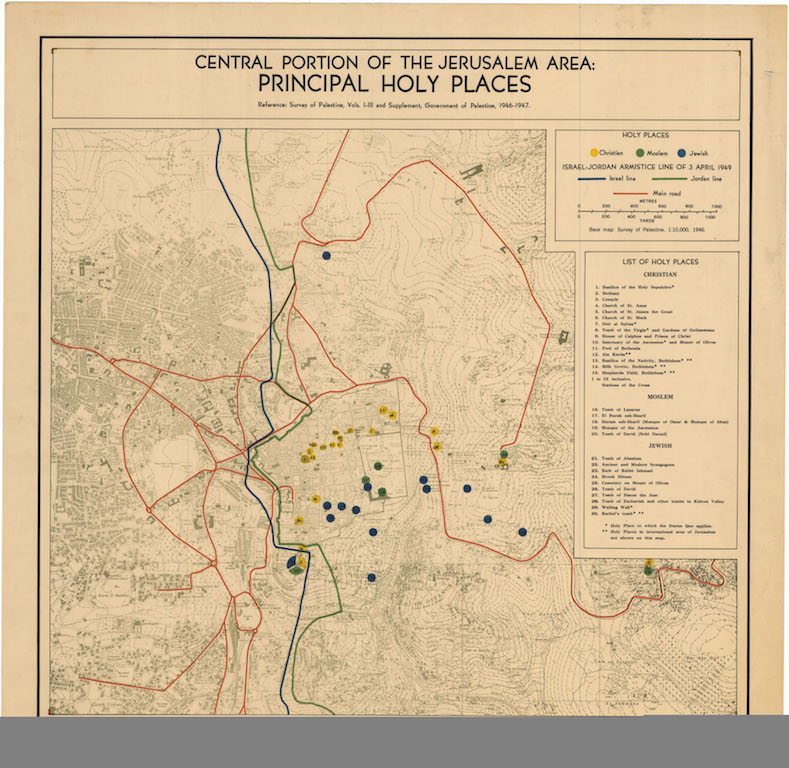

[This translation is an excerpt of Jabra Ibrahim Jabra’s twenty-page essay, “Jerusalem: Time Embodied.” It was published by the Modern Library (al-Maktaba al-‘Asriya) press in Beirut in 1967 in a collection of his literary and social criticism entitled, The Eighth Journey. Jabra wrote these recollections of his childhood in Jerusalem before the 1967 war when what we now call East Jerusalem was annexed by Israel. Until Israel captured these neighborhoods (along with the West Bank and Gaza) during that conflict, Jerusalem had been a divided city for 19 years. The United Nations map below (and here, in greater detail) shows some of the places that Jabra mentions. Other landmarks, like the offices of Boulous Saeed, a publisher and the grandfather of Professor Edward Said, are not marked.]

The city of Jerusalem is not just a place; it is also a time. One cannot understand it only in its limited physical boundaries. It must be seen in its historical perspective, as if it were history itself. As if an observer might grasp the history of four thousand years in a single glance.

In this city, history lives. Every stone pronounces it. This history is full of contradictions, full of disasters, but it is also the story of a city for which all of humanity has yearned. Because it has never been, not for one day, merely a city composed of stone and dirt, business and politics. It has always been a city of dreams and longing, and of the human spirit’s gaze toward God. The city has stood as a tower on a mountain. On the one side, it looks towards the sea. On the other, toward the barren desert. And between its walls, the city joined together both of these spirits, these two civilizational forces—the sea and the wilderness—in a never-ending back and forth. This interplay is the secret of its tragedy and of its greatness.

Originally and until the end of the last century, Jerusalem was the walled city with its seven gates. It began to spill over these walls more than seventy years ago when, bit by bit, it started to reach the suburbs surrounding it on all sides. This expansion accelerated after the destruction of a section of the wall at Jaffa Gate in 1898. Only then was the core, walled city organically tied to its extensions.

The oldest extension of the city outside the walls lies in the Nabi Dawood area, south of the city. It goes back several centuries, unlike the larger extensions of the city that were completed in one moment between 1920 and 1948 to the north, west, and south.

The new parts of Jerusalem sprung up then. They extended on one side along Jaffa Road, and from the other, along Mamilla Street and Ma’man Allah Cemetary, and after the YMCA was built in the 1930s, along St. Julian Street. In this way, ties were built between the distant boroughs of new Jerusalem and the old city itself.

In the middle of the nineteenth century, the Germans established a colony a few kilometers from the walls. A Greek colony followed. Then, monasteries and neighborhoods appeared here and there belonging to Catholics and Roman Orthodox and others. Jewish neighborhoods began to spring up, funded by the Englishman, Moses Montefiore. Until the end of the twenties, the neighborhoods of Fawqa, Talbiyya, and Katamon, were owned by individuals from Jerusalem and Bethlehem and had been little more than recreation spots for Jerusalemites. However, in the thirties, these lands were surveyed and developed in one massive tract that encircled the walled city on most of its sides. With that, the establishment of modern Jerusalem with its two parts—the old and the new—was complete. Similarly, in just a few years, the desert regions scattered with houses and filled with olive groves, transformed into upscale neighborhoods with stone buildings and many gardens, all of modern design.

Now, the first thing that the observer must say about Jerusalem is that it is an Arab city—Arab to the core!—even though Zionists occupied its new half. The new half under occupation remains as Arab as its old half does, as Arab as the rest of occupied Palestine. When one of Jerusalem’s children speaks about his city, it is impossible for him to restrict himself to the walled city and to the buildings and expansions that have appeared around it in the period after the Nakba.

For Jerusalem is a single, natural entity whose separation is as illogical as it is criminal. The division of Jerusalem is but a miniature version of the insanity that arbitrarily partitioned one piece of Palestine for the Jews. Years have passed since this injustice, but the Jerusalemite will never imagine his city without the occupied half, with its Arab neighborhoods, Arab houses, and Arab color.

Because of this, I do not see anywhere to start but from a purely personal perspective.

I lived in a low area outside of the wall under the heights of Nabi Dawood that was known by the name “Jawrat al-Enaab.” It was one of those first neighborhoods that sprung up outside of Jerusalem at the turn of the twentieth century. I have seen its transformation—it used to have an animal market every Friday, and turned into an industrial area with blacksmith, carpenter, and plumbers’ shops. In the early thirties, I worked there for two consecutive summers during summer vacation, earning two and a half piasters a day.

Our home was a single room in a big building whose ground floor lay beneath the main street. It was made up of an uncovered, square courtyard you reached by a staircase. On each side was a room. In each of these, lived an entire family. From the door of our room I could see the minaret of Nabi Dawood looming over us from its great height. There was only one small window next to the door leading out to the courtyard—and we would pile our books and school things in it. The landlord let us open a small square hole at the top of the back wall to help ventilate the place. The opening was exactly at the ground level of the main street. There was no asphalt in those days, so we put a metal screen and a small curtain over it. I was in the habit of waking before dawn to the voices of the peasant women coming from the surrounding villages carrying baskets of vegetables to the market. They would sit close to that window as they rested from their arduous walk up to the vegetable market at Jaffa Gate. They and their donkeys made a huge racket.

On school days I would climb out of the “pit” we lived in and go up to Jaffa Gate. The place was awash with cars and buses, crates of fruit and vegetables, and of course, sellers and buyers and porters. Then, I would go to the Rashidiyya School—which still stands in its place outside of Herod’s Gate—either by way of Hebron Gate and the old city or by way of Jaffa Road. Then I would climb to the Old Post Office, passing by the office of Boulous Saeed. Then I would descend Aqbat al-Manzil passing by the New Gate and the French Hospital, which is attached to Notre Dame Monastery. Then I would pass by Musrara to Damascus Gate. But today, all of this is part of the forbidden zone full of debris and barbed wire. Looking west from Damascus Gate, you see the big monastery across the wires. It was destroyed and abandoned after the violent battle that took place there between Arab and the Jewish forces in 1948. Jewish units wanted to use the monastery as a platform from which to attack Damascus Gate and invade the old city. The fighters and the Arab armies defied them. After a fierce confrontation, they were driven back.

We moved after that to a different neighborhood between Mamilla Street and Shamaa. Before the famous general strike in 1936, Jerusalem had been growing rapidly. After the strike, the city’s expansion resumed. In this period, the Arab College was built on Mount Scopus, south of the city. Its provost was the Professor Ahmad Samih al-Khalidi, God have mercy on him. After riding the bus, I would get off and walk south, behind the British military base, arriving at the top of Mount Scopus where the college sat in the middle of a wide-open expanse, some of it composed of sports fields. Around the edges, hundreds of pine seedlings had been planted. Between 1935 and 1938, we watched those trees grow.

I spent my last year inside at the Arab College, and I will never forget the view of Jerusalem across the Valley of Rababa. In the day the city was covered with purple clouds. At night it gleamed and lit up.

In those days, about 120 students attended the Arab College, and they were selected from among the very best graduates of Palestine’s schools. This remained the case until the Nakba. Apart from their intelligence, most of the students were distinguished by an amazing capacity for intense study. One of the duties of the administration was to restrain students from the desire to continue all-night “secret” study in their beds after the lights had gone out! It is not surprising that a large number of the young men that graduated from the college went on to become famous in the Arab world. At night, we would gaze across to Jerusalem from there, our place of devotion. On that same mountain, thirteen hundred years before us, ‘Umar bin al-Khattab had stood to look upon the holy site for the first time. “A chain of chandeliers stretching to the stars in the heavens.” That is how we would describe the city, radiant in the darkness, across the valley that was called in times past the Valley of Jehenem (Hell). We would talk and talk about the things that young people talk about¬—especially literature and politics, not to mention our ferocious lessons that some of us would memorize by heart, by walking around and around the huge playing fields, “cramming” endlessly.

A few years later, we moved again, this time west, to the suburb of Katamon. It was on the summit of a hill that overlooked rocky slopes on one side – that reached a valley with the road that leads to the village of Maliha – and on the other side, slopes full of the beautiful, stone houses for which Jerusalem is known. Now, in the beginning of 1947, the city had reached its greatest extent and splendor, even though three years prior, the Jewish terrorists had a brutal plan to destroy the new Jerusalem. They began first by blowing up government buildings, one after another, including, famously, the King David Hotel, seat of the Mandate government. After the UN Partition was announced in November 1947, they began to blow up Arab houses at night. In Katamon it was particularly bad, since it abutted the Jewish neighborhood of Rehavia. Residents of Katamon were terrorized, and began to flee. Arabs responded to the provocations, and a few months later, new Jerusalem had become a terrifying labyrinth of barbed wire, abandoned houses, and scattered ruins. Bullets snarled back and forth day and night.

As for me, I remember the new Jerusalem—the Jerusalem that was stolen from us—much as Adam remembered the Garden of Paradise. As I grew up, the city grew up with me. My childhood was a reflection of its hundreds of roads, houses, stores, alleyways, and trees. It echoed the gardens that bloom in the spring and wither in the winter, and the many scattered rocks that make up this city. Where does my self end and the subject of my discussion begin here? A street is where this boy cried, where he grew hungry, where he laughed, and where he longed for a girl whose name he never knew because she smiled at him without meaning to. A city street is where this boy ran through the rain. This is where he sat in the dark with his brothers, with his parents, with tens of his friends whose voices he can still hear in his mind ringing between the buildings. Could such a street remain merely an objective, technical extension?

When an enemy comes and crushes sidewalks with armored cars, when he blows up houses with everyone in them, when he tears family and friends up from their roots, when he casts a boy—now a young man—across valleys and deserts, from one road to another, from one home to another, is this not a brazen attempt to sever Self from Self?

From this experience comes every Palestinian’s feeling that he must return. Return is more than a reclamation of the land stolen by an enemy. It is winning back that part of the Self that had been taken, and returning it to itself so it can be whole again.